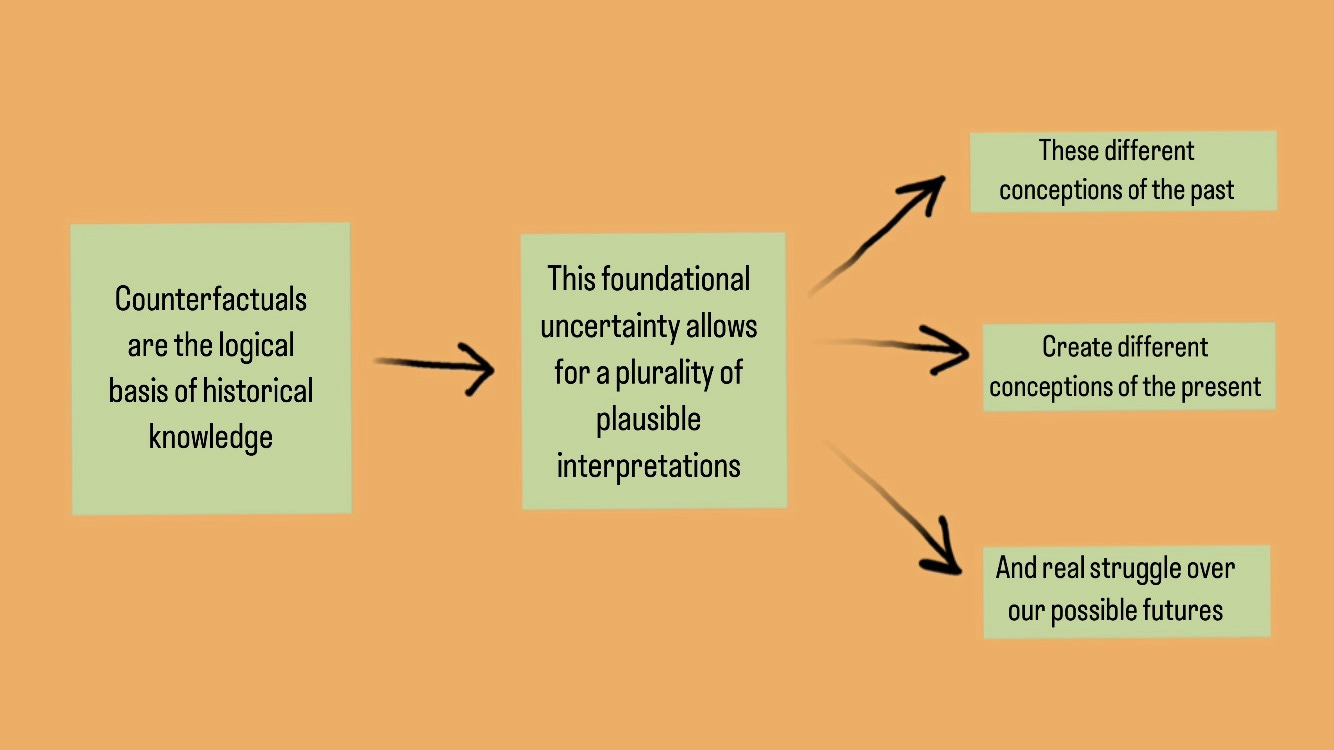

The various uses of Historical Materialism are as contradictory as the class forces they claim to explain. For some, historical materialism is an objective, scientific account of the past.1 By studying real material forces, it explains why the past had to happen, and where it has to go. But this ‘productive force determinism’ is just one possible interpretation, and is contradicted by history’s counterfactual foundations.2 As I show in this essay, all historical arguments about causation, and all conscious decision making, depend on imaginary ‘what if’ scenarios. These counterfactual limitations render historical materialism inherently uncertain. Instead of a single, scientific account of the past, historical materialism allows for a plurality of plausible interpretations. To understand history ‘objectively’, then, is to appreciate a constantly changing struggle. There is always a multitude of attempts at a theoretically sound, and historically valid, interpretation of our past, present and futures. This is a good thing, though. It allows historical materialism to study all available options. Rather than giving orders, counterfactual materialism encourages socialists and workers to create their own history.

Counterfactuals are necessary for understanding the world, and for changing it.

Historical materialism has counterfactual foundations.

To some, including some of the greatest, history’s counterfactual foundations should be ignored. History is the study of the past, of what actually happened. There is no place, then, for what ‘might-have-been’. This was the view of the brilliant Marxist historian, E.H. Carr. In his classic work, What is History?, Carr claimed that counterfactuals were a symptom of people remembering ‘the time when all the options were still open’. This prevents them from adopting ‘the attitude of the historian for whom [the options] have been closed by the fait accompli.’ Importantly, we can agree with Carr that the past couldn’t have happened otherwise. But this philosophical qualification, on its own, misses the point. Historians must imagine counterfactuals, whether implicitly or otherwise. They must, not because things actually could have happened differently, but because counterfactuals are the logical basis of all causal claims. Even more importantly, it is the historian’s job to appreciate that ‘time when all the options were still open’. Our knowledge of why things actually happened depends on it.

From counterfactual logic to counterfactual struggle

We can show the counterfactual basis of any argument about historical causation by using fancy italicised letters. Let’s suppose that:

a caused b.

This might not seem like a counterfactual, but it implies that:

if a had not happened, neither would b.

This is counterfactual logic in its abstracted, ahistorical form. To see it used historically, I’ve paraphrased the late great Eric Hobsbawm:

[The Great Depression] caused [World War II]. Therefore, if [The Great Depression] had not happened, neither would have [World War II].

This historical counterfactual presents a dilemma. Hobsbawm couldn’t go back in time. He was never able to stop The Great Depression, so never proved his causal claim. This is why he presented it only as a possibility. He wrote that World War II:

‘might have been avoided, or at least postponed, if the pre-war economy had been restored again as a global system of prosperous growth and expansion.’

Here, Hobsbawm appeals to an imaginary timeline that our consciousness has no access to. Still, the counterfactual is deeply rooted in historical evidence. Hobsbawm explains that The Great Depression allowed the Nazi party to conquer state power. From this moment a:

‘new world war was not only predictable, but routinely predicted. Those who became adults in the 1930s expected it.’3

By embedding his counterfactual with historical evidence, Hobsbawm showed its existence as real historical consciousness. Real people, in the 1930s, agreed with his causal claim, and used it to successfully predict a second world war. Clearly, then, Hobsbawm’s counterfactual is historically valid. It is theoretically sound, and accords with the available evidence.

Still, Hobsbawm’s counterfactual isn’t proven. Maybe the people in the 1930s were wrong. Maybe there were things that could have been done to avoid Hitler’s rise to power, even if the pre-WWI global economy had not been restored. This was the view of C.L.R. James, writing in 1937. By tracing several strategic possibilities, he argued that the Nazis could have been defeated even with the Great Depression.4 James explained Hitler’s rise as a failure of socialist strategy, and attributed this to the Stalinist distortion of the Communist International.5 Without the Communist International’s interventions, Germany’s socialists and workers might not have been divided, and could — James argued — have defeated the Nazis.6 The results would have been momentous:

‘If the German proletariat were victorious, it meant the almost immediate victory of the Austrian proletariat. Fascism in Italy would receive a most serious blow. In Spain the revolution which had broken out in 1931 would receive an enormous impetus and an enthusiastic ally. Most important of all, the bogey of German invasion, which is the main threat that French Capitalism uses to the French workers, would disappear at a stroke, and the French bourgeoisie would be jammed between the German working-class movement and its own. The difficulties of economic construction in the Soviet Union would have been solved by the combination of Soviet natural resources and Germany’s marvellous industrial organisation — that alliance which Lenin had so hoped for.’ p. 317.

Liberals largely agree with Hobsbawm, but like C.L.R. James, go deeper. They answer Hobsbawm’s question by noting decisions that might have ‘restored the pre-war economy’. Keynes, for example, quit the 1919 Paris Peace Conference, claiming that its decision to punish Germany would be catastrophic for Europe:

‘If the European Civil War is to end with France and Italy abusing their momentary victorious power to destroy Germany and Austria-Hungary now prostrate, they invite their own destruction also, being so deeply and inextricably intertwined with their victims by hidden psychic and economic bonds.’ [Keynes, 1919, p. 5]

Here Keynes, like C.L.R. James, was using counterfactuals for a strategic purpose. As historical actors, they sought knowledge of the world in order to change it. In fact, Keynes’ counterfactual did change the world. By co-leading the post-WWII Bretton Woods conference, he helped design a world order based on his counterfactual analysis of the the inter-war crisis.7

By highlighting Hobsbawm’s counterfactual logic, I showed the inherent uncertainty of all historical claims about causation. This allowed for an appreciation of a plurality of plausible interpretations of the past, and a plurality of strategic options. The counterfactuals of C.L.R. James were used to advocate a return to Leninism. Keynes’ counterfactuals were used to rebuild a post-war liberal imperialism.

Counterfactual Dual Power

None of this, of course, is new. Despite the protestations of counterfactual-phobes, imaginary ‘what if’ scenarios have always been essential to historical knowledge and historical action. The best historical materialists were well aware of this, including — as I show in a later post — Karl Marx. It is illustrated more obviously, though, in Leon Trotsky’s History of the Russian Revolution. There, he wrote as both historian and historical subject.8 Take this particularly striking moment, where Trotsky defends Lenin’s decision to lead an insurrection:

‘A revolutionary situation cannot be preserved at will. If the Bolsheviks had not seized the power in October and November, in all probability they would not have seized it at all. Instead of firm leadership the masses would have found among the Bolsheviks that same disparity between word and deed which they were already sick of, and they would have ebbed away in the course of two or three months from this party which had deceived their hopes, just as they had recently ebbed away from the Social Revolutionaries and Mensheviks. A part of the workers would have fallen into indifferentism. Another part would have burned up their force in convulsive movements in anarchistic flare-ups, in guerrilla skirmishes, in a Terror dictated by revenge and despair. The breathing-spell thus offered would have been used by the bourgeoisie to conclude a separate peace with the Hohenzollern, and stamp out the revolutionary organisations. Russia would again have been included in the circle of capitalist states as a semi-imperialist, semi-colonial country. The proletarian revolution would have been deferred to an indefinite future. It was his keen understanding of this prospect that inspired Lenin to that cry of alarm: “The success of the Russian and world revolution depends upon a two or three days’ struggle.” ’ p. 730

According to Trotsky, the October Revolution didn’t cause a civil war, or end the bourgeois republic. That would have happened anyway.9 What it did was prevent the impending civil war from being led and won by a reactionary militarism. In other words, without the insurrection things would have been worse. This is a powerful defence. With it, Leninists and Anarchists (who also supported and participated in the insurrection) can support a tactic that led, ultimately, to Stalinist betrayal and monopoly capitalist encirclement. For even without going into the complex chains of causation that followed the October Revolution, this one simple counterfactual absolves all. The alternative would have been worse.

Importantly, though, Trotsky’s counterfactual is more than just a retrospective justification. According to Trotsky, this counterfactual formed the very logic that drove the decision to lead the insurrection in the first place. If it wasn’t for Lenin’s ‘keen understanding of this prospect’, there mightn’t have been an October Revolution at all. Without imaginary ‘what if?’ scenarios, in fact, there can be no conscious decision making at all.10 For consciousness creates history, but it does so within conditions that it doesn’t choose. One of those conditions is the uncertainty of the future. When faced by a decision, the best a person can do is create theoretically sound, and historically valid, scenarios. What are the likely results of the available options? This is the prime goal of counterfactual materialism, and it can be seen, already, with Lenin’s decision to lead an insurrectionary coup, arguably the most important decision making moment in the history of class struggle.

Yeah, but who cares?

If historical materialists, like Trotsky, already use counterfactuals, then what is the point of this essay? What is the point of a self-conscious awareness of historical materialism’s counterfactual foundations? It helps avoid two main problems: pseudo-certainty, and selectivity. Trotsky, for example, used counterfactuals throughout his work and revolutionary praxis. Still, he maintained a belief in ‘the laws of revolution as an objectively conditioned process’. Marxism was the ‘scientific discovery of these laws’ which ‘govern the movement of the popular masses’.11 For Trotsky, there was a correct, scientific understanding of how things came to now, and where they’re going. Counterfactuals were used to defend his own position, a position which is taken to be objectively, and scientifically true. However, history’s counterfactual limitations challenge this entire philosophy of history. Can Trotsky be sure that alternative counterfactual scenarios, equally imagined, are false? No. The very counterfactual basis of historical knowledge makes certainty impossible.

This isn’t a flaw unique to Trotsky. It is present in all socialist strategic traditions. They all use counterfactuals, but usually selectively. When a historical materialist analyses a rival tendency, they revert to a crude empiricism. Different strategic traditions, in theory and practice, are dismissed. Their flaws are irrefutably “proven” by the “simple historical fact” that all other socialist projects have failed. This crude empiricism vanishes, however, when one considers their own strategic lore. Then, like with Trotsky, the fully-nuanced counterfactual analysis kicks in. There are two counterfactuals that do the most heavy lifting:

My strategy failed, but things would have been far worse without it.

Or:

My strategy failed, but it could have succeeded, if only this or that decision was made ever so slightly differently.

Tracing history’s counterfactual foundations allows us to step back, to see that all socialist projects depend on counterfactuals. All are uncertain, and all have variously failed, but that’s fine. The task of historical materialism is not to objectively determine which is the correct strategy. It is to consider all strategies that are theoretically sound, and historically valid. That’s what a self-conscious appreciation of history’s counterfactual limitations provides. It allows us to consider, and compare, a plurality of historical materialisms.

Crucially, this pluralistic approach is not some abstract exercise in “academic Marxism”. It is essential for socialist praxes. For if there was one correct position, ordained by science, there would be no need for democratic processes. There would be no need to weigh up the different strategic options. As such, an appreciation of history’s counterfactual foundations is an important defence against such unjustified authority. History can’t know a single, scientifically-correct account of the past, present or futures. What it can offer is a plurality of theoretically sound, and historically valid, historical materialist imaginaries. With such a framework, historical materialism can consider and compare all revolutionary possibilities, or strategic choices. What workers and socialists do with this, though, is entirely up to them.12

Counterfactual Materialism is continued in subsequent posts where I:

explore the uses and abuses of counterfactuals by socialists during the October Revolution

show how Marx used counterfactuals in his Law of the Tendential Fall in the Rate of Profit to outline a plurality of possible futures

As Eric Hobsbawm explained of the history group of the communist party in the 1950s:

‘Politics then often insisted a priori on the 'correct' interpretation, which it was the business of Marxist theory to 'prove', i.e. to confirm.’

also:

John Holloway, The Tradition of Scientific Marxism

“For Engels, the claim that Marxism is scientific is a claim that it has understood the laws of motion of society. This understanding is based on two key elements: ‘These two great discoveries, the materialistic conception of history and the revelation of the secret of capitalistic production through surplus-value, we owe to Marx. With these two discoveries Socialism becomes a science. The next thing was to work out all its details and relations.’

Science, in the Engelsian tradition which became known as ‘Marxism’, is understood as the exclusion of subjectivity: ‘scientific’ is identified with ‘objective’. The claim that Marxism is scientific is taken to mean that subjective struggle (the struggle of socialists today) finds support in the objective movement of history. The analogy with natural science is important not because of the conception of nature that underlies it but because of what it says about the movement of human history. Both nature and history are seen as being governed by forces ‘independent of men’s will’, forces that can therefore be studied objectively.

The notion of Marxism as scientific socialism has two aspects. In Engels’ account there is a double objectivity. Marxism is objective, certain, ‘scientific’ knowledge of an objective, inevitable process. Marxism is understood as scientific in the sense that it has understood correctly the laws of motion of a historical process taking place independently of men’s will. All that is left for Marxists to do is to fill in the details, to apply the scientific understanding of history.”

Or

Frederick Engels, Socialism: Utopian and Scientific, Part III: Historical Materialism:

‘From this point of view, the final causes of all social changes and political revolutions are to be sought, not in men's brains, not in men's better insights into eternal truth and justice, but in changes in the modes of production and exchange. They are to be sought, not in the philosophy, but in the economics of each particular epoch. The growing perception that existing social institutions are unreasonable and unjust, that reason has become unreason, and right wrong [1], is only proof that in the modes of production and exchange changes have silently taken place with which the social order, adapted to earlier economic conditions, is no longer in keeping.’

and

‘And this conflict between productive forces and modes of production is not a conflict engendered in the mind of man, like that between original sin and divine justice. It exists, in fact, objectively, outside us, independently of the will and actions even of the men that have brought it on. Modern Socialism is nothing but the reflex, in thought, of this conflict in fact; its ideal reflection in the minds, first, of the class directly suffering under it, the working class.’

Also:

John Holloway, The Tradition of Scientific Marxism:

“At one extreme was the position usually identified with the Second International, and formulated most clearly by Cunow at the end of the 1890s (Cunow 1898-99): since the collapse of capitalism was the inevitable result of the working out of its own contradictions, there was no need for revolutionary organisation. Those who argued that the collapse of capitalism was inevitable did not all draw the same conclusions, however. For Luxemburg, as we have seen, the inevitable collapse of capitalism (which she attributed to the exhaustion of the possibilities of capitalist expansion into a non-capitalist world) was seen as giving support to anti-capitalist struggle rather than detracting from the need for revolutionary organisation.”

This view implies that only highly educated socialists can understand the one true scientific account of history, and must teach and lead the rest. But if history was to be scientific, it would need to be conscious of how historians, as consciousness, create knowledge:

“The central issue is rather the concept of science or theory which was accepted by the main stream of the Marxist movement. If science is understood as an objectively ‘correct’ understanding of society, then it follows that those most likely to attain such an understanding will be those with greatest access to education (understood, presumably, as being at least potentially scientific). Given the organisation of education in capitalist society, these will be members of the bourgeoisie. Science, consequently, can come to the proletariat only from outside. If the movement to socialism is based on the scientific understanding of society, then it must be led by bourgeois intellectuals and those ‘proletarians distinguished by their intellectual development’ to whom they have transmitted their scientific understanding. Scientific socialism, understood in this way, is the theory of the emancipation of the proletariat, but certainly not of its self-emancipation. Class struggle is understood instrumentally, not as a process of self-emancipation but as the struggle to create a society in which the proletariat would be emancipated: hence the pivotal role of ‘conquering power’. The whole point of conquering power is that it is a means of liberating others. It is the means by which class-conscious revolutionaries, organised in the party, can liberate the proletariat. In a theory in which the working class is a ‘they’, distinguished from a ‘we’ who are conscious of the need for revolution, the notion of ‘taking power’ is simply the articulation that joins the ‘they’ and the ‘we’.”

And

“The Engelsian concept of science implies a monological political practice. The movement of thought is a monologue, the unidirectional transmission of consciousness from the party to the masses. A concept that understands science as the critique of fetishism, on the other hand, leads (or should lead) to a more dialogical concept of politics, simply because we are all subject to fetishism and because science is just part of the struggle against the rupture of doing and done, a struggle in which we are all involved in different ways. Understanding science as critique leads more easily to a politics of dialogue, a politics of talking-listening, rather than just of talking.”

I take the term ‘Productive Force Determinism’ from Søren Mau’s Mute Compulsion: A Marxist Theory of the Economic Power of Capital. He gives a pithy summary of its history:

‘The doctrine of historical materialism was further developed by influential Marxists such as Karl Kautsky, Franz Mehring and Georgi Plekhanov. The economy, conceived as a distinct social sphere, was proclaimed to be the basis or infrastructure and thus primary in relation to the ideological, political and legal superstructures. This basis was a ‘mode of production’, a totality made up of the (unstable) unity of two moments: the productive forces and the relations of production. Historical development was then conceived as a succession of modes of production driven forward by a dialectic of productive forces and relations of production. The contradiction between these arises because of the immanent and necessary progress of technology, conceived as a transhistorical force necessarily colliding with the historically specific social relations attempting to contain it. Historical materialism was thus a determinist philosophy of history in which historically specific social formations were, in the last instance, reduced to a stage in the unfolding of a transhistorical technological rationality. ‘The productive forces at man’s disposal determine all his social relations’, as Plekhanov put it (1971, p. 115). Kautsky likewise held the ‘development of technology’ to be ‘the motor of social development’, providing a scientific basis for proletarian struggle: ‘with the progress of technology not only the material means are born that make socialism possible but also the driving forces that bring it about. This driving force is the proletarian class struggle [...] It must finally be victorious due to the continuous progress of technology’ (Kautsky, 1929).

The determinism of historical materialism was exacerbated by scientistic positivism. In the preface to A Contribution, Marx had claimed that economic analysis could be conducted with ‘the precision of natural science’. In the preface to Capital he had written about the ‘iron necessity’ of ‘the natural laws of capitalist production’ (C1: 91). Marx’s understanding of nature was shaped in a context influenced by German Idealism which saw no opposition between speculative philosophy and natural science (Foster & Burkett, 2000). By the time these remarks were taken up by the early Marxists, the intellectual milieu had changed. Speculative Naturphilosophie had been replaced with empirical science, and nature had come to mean an ‘objective’ world outside of human thought ruled by transhistorical laws. At Marx’s funeral, Engels famously likened Marx to Darwin. While the latter had ‘discovered the law of development of organic nature on our planet’, Marx was cast as ‘the discoverer of the fundamental law according to which history moves’ (24: 463). This was picked up by Kautsky, who pushed historical materialism further in the direction of an evolutionist philosophy of history. In this context, Marx’s remarks about the ‘natural laws’ of capitalism was taken as a justification of the introduction of a positivist paradigm for social science (Elbe, 2008, p. 14ff; Eley, 2002, p. 45; Foster, 2000, p. 231; Kolakowski, 1990, p. 32). 13’ pp. 52-53.

Eric Hobsbawm, The Age of Extremes, p. 35.

C.L.R. James, World Revolution 1917-1936: The Rise And Fall Of The Communist International, (1937):

‘If Brandler had met in Moscow, not Stalin, the advance-guard of Revisionism, but revolutionary Socialism incarnate in Lenin, there would have been a revolution in Germany in 1923. A defeat might have been the result. But a defeat in 1923 would have been the surest preparation for the new upsurge a decade or so later. The inaction of 1923 hung heavily over pre-Hitlerite Germany. There are accidents in history. Cleopatra’s nose might have been shorter, and a stray bullet might have killed General Bonaparte. The broad outlines of history would have remained unchanged. But we who live today in a period where a revolutionary defeat or victory affects in the most literal sense the lives of half the world’s inhabitants, cannot afford to be too philosophical about the reasons which made for success or failure. Leninism is the only solution to the problems of the modern world. It might have saved us another world-war on the scale of the one which approaches. But there was too much need of Lenin in both the planning and the execution of Leninism.’ p. 211.

C.L.R. James, World Revolution 1917-1936: The Rise And Fall Of The Communist International, (1937):

‘That the German workers went down without a struggle when they had an even chance of victory was no fault of theirs. They were ruined by the ignorant and treacherous Soviet bureaucracy.’ p. 324.

And:

‘The workers had organised themselves into the Reichsbanner, ready to fight for the defence of the republic. It was all that the Communists needed. They, while not identifying themselves with the fight for the republic, could fight side by side with the Social Democrats against Fascism. That road, as we see in Catalonia today, could lead only to the struggle for the dictatorship of the proletariat, the Social Democratic workers being driven to take it, not by propaganda but by the very logic of events. But for the Communists Hitler was the lesser evil. Destroy the Social Democracy, the dirty Social Fascists.’ p. 326.

C.L.R. James, World Revolution 1917-1936: The Rise And Fall Of The Communist International, (1937):

‘The German Communist Party votes in 1930 had jumped from 3,300,000 to 4,600,000, nothing in comparison to the Fascist increase. But in Germany, with twenty-five large towns of over 500,000 people, with the workers dominant in the economy of the country, the combined Communist and Social Democratic vote represented the dominant social force in the country.

…

With the policy of the United Front against Fascism, the Social Democratic worker, step by step, could be led on the basis of his own experience to fight against Fascism; and the victorious struggle against Fascism, not in parliament, but in the streets, would lead directly to power.’ p. 320.

And:

‘That the German workers went down without a struggle when they had an even chance of victory was no fault of theirs. They were ruined by the ignorant and treacherous Soviet bureaucracy.’ p. 324.

As leader of the British delegation to the post WWII Bretton Woods conference, Keynes was the co-author of the ‘Bretton Woods system’ of international trade. This system was designed with the liberal counterfactuals of the inter-war crisis in mind. Liberals attribute a large part of the global crisis to a failure of US leadership, pointing to the failure of the International Economic Conference of 1927, and the US Smoot Hawley Tariff. By Turning against multilateral solution to the then trade war, the US cemented a beggar-thy-neighbour tariff race. This is believed to have deepened The Great Depression. Without this, and without post-WWI punishment of Germany, liberals believe Nazism wouldn’t have risen to power. At Bretton Woods, these liberal counterfactuals were used to justify the creation of the General Agreement on Tariffs and Trade (GATT), an institution that would eventually become the World Trade Organisation.

Keynes counterfactual, which he famously wrote in the Economic Consequences of the Peace, was also formative. The World Bank, and US loans like The Marshal Plan, were set up to stimulate post-war recovery, in a stark contrast to the disciplinary measures decided at the 1919 Paris Peace Conference.

Of course, the precise causal effect of the post-WWII Bretton Woods system is hard to gauge. The decades that followed are widely considered to be a Golden Age of Capitalism, but this doesn’t imply that the Bretton Woods System caused it. More likely, the golden age was caused by a long wave of post war expansion, which would have boosted growth regardless.

What’s more, many of Keynes’ ideas were rejected by the US delegation, including a new international means of payment, the Bancor. An entire counterfactual critique from The Global South, or The Third World Project, was thus born. What if the states of the global south had all been independent at the Bretton Woods conference? This critique Carrie’s forwards to the struggle, in the 1970s, for a New International Economic Order.

Trotksy was a historical materialist of the highest order, and deeply aware of history’s counterfactual foundations. Even more important, however, is his role as historical subject, a conscious actor in the Russian Revolution who — with Lenin — relied on a counterfactual materialism of the highest order.

Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution:

‘“Either Kornilov or Lenin”: thus Miliukov defined the alternative. Lenin on his part wrote: “Either a soviet government or Kornilovism. These is no middle course.” To this extent Miliukov and Lenin coincided in their appraisal of the situation—and not accidentally. In contrast to the heroes of the compromise phase, these two were serious representatives of the basic classes of society. According to Miliukov, the Moscow State Conference had already made it clearly obvious that “the country is dividing into two camps, between which there can be no essential conciliation or agreement.” But where there can be no agreement between two social camps, the issue is decided by civil war.’ Pp. 608-609.

and:

‘The bourgeois press, led by the Kadet organ Rech, was asserting every morning that we must not “let the Bolsheviks choose the moment for a declaration of civil war.” That meant: We must strike a timely blow at the Bolsheviks.’ p. 682.

Good for the Graeber quote I had before.

Trotsky, History of the Russian Revolution:

‘What distinguished Bolshevism was that it subordinated the subjective goal, the defence of the interests of the popular masses, to the laws of revolution as an objectively conditioned process. The scientific discovery of these laws, and first of all those which govern the movement of popular masses, constituted the basis of the Bolshevik strategy. The toilers are guided in their struggle not only by their demands, not only by their needs, but by their life experiences. Bolshevism had absolutely not taint of any aristocratic scorn for the independent experience of the masses. On the contrary, the Bolsheviks took this for their point of departure and built upon it. That was one of their great points of superiority.’ p. 581.

Even this, I should stress, is not new. Counterfactual Materialism, defined as a historical materialism aware of its counterfactual foundations, has provided some of the greatest works of revisionist history. I cite C.L.R. James’ Black Jacobins as a classic example, in so far as he uses counterfactuals to trace the strategic decision making that guided the fate of the Haitian Revolution.

More recently, is Silvia Federici’s Calaban and the Witch, which reconsiders feudal power by imagining that capitalism needn’t have happened at all.